The success of Winx shows the value of symmetry in race horses

Source: TheConversation.com /

As Australia prepares to farewell the beloved racehorse Winx in her final race this weekend, it’s interesting to look at the factors that contributed to her incredible success.

This magnificent mare’s extraordinary career reflects her impeccable genetics, rearing, training, strategic rest periods, and race riding. Optimal heart, lung and muscle function also play a part.

But what about something we refer to as her “economy of locomotion” during high-speed galloping? This is the energy cost of travelling a particular distance.

This can be compromised during a race, both by behavioural factors such as “pulling” due to overexcitement, and by any bias in the horse towards one side over the other, known as structural asymmetry.

We don’t know whether Winx has perfect structural symmetry. But her trainer and regular riders would have a strong sense of the mare’s balance during track work and races.

A matter of left and right

Bilateral symmetry in animals refers to the balance of structures, such that they are mirror images along the body’s midline.

Asymmetry is a disruption of the left-right balance that may be associated with factors such as abnormal anatomy, chronic lameness, or laterality (a preference to use one side of the body rather than the other).

In horses, there is now evidence from laterality studies of differences in and between populations due to age, training, handling, breeding, sex, arousal and anatomical proportions, such a ratio of head length to leg length.

Racecourses vary from state to state

Horse racing in Australia is rarely done only in a straight line. In New South Wales and Queensland, for example, horses race in a clockwise direction, whereas in Victoria they race anticlockwise.

Winx has raced and won mostly in NSW but has also won four Cox Plates (Victoria), so clearly she can cope with both track directions.

For many others, race direction can matter and may risk injury to a horse.

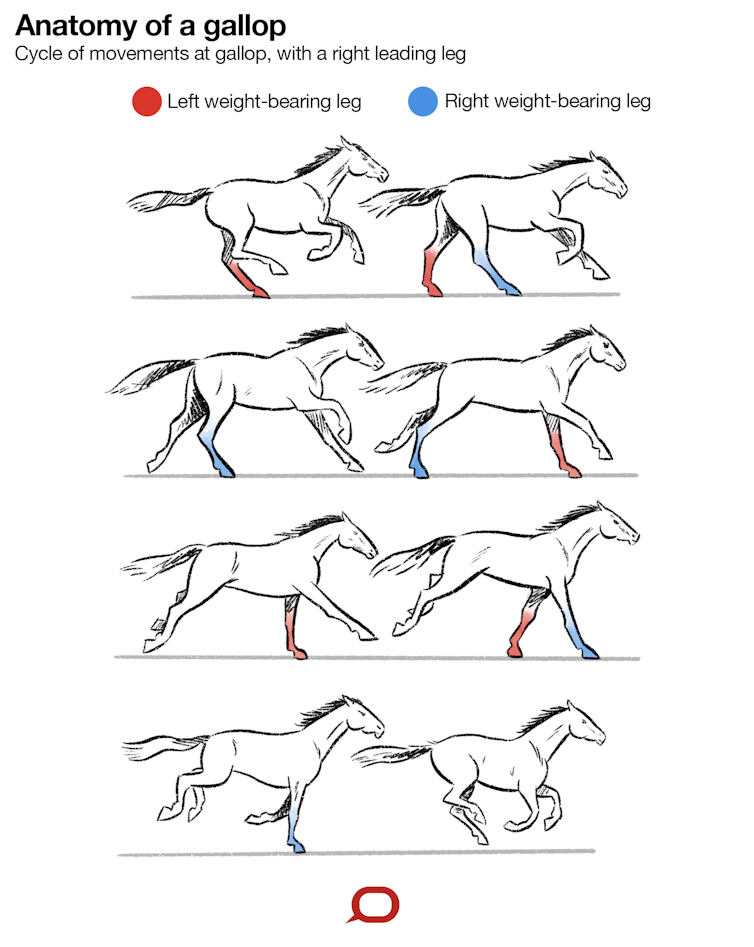

On bends, it is common for horses to use the left leading leg when galloping in an anticlockwise direction, and vice versa. But, because of asymmetry, many horses have a preferred leading leg. So, depending on the state, the bends favour some horses more than others.

The direction of racing predicts which limbs are vulnerable to injury.

Irrespective of course direction, one study found 72% of musculoskeletal injuries occur to the leading leg. Major sites on a racetrack of injury were:

- on the straights (30.77% of injuries involved the leading leg)

- coming out of a turn (55.31% of injuries were to the leading leg)

- passing a turn (62.5% of injuries corresponded with the leading leg)

This implies that more strain is put on the leading leg during turns.

Therefore, horses racing on their weaker side, in a direction counter to their preferred leading leg, may be at increased risk of injury.

Asymmetry is normal in horses

Sizeable anatomical asymmetries can affect a horse’s race performanceand, beyond a certain point, can lead to lameness.

Thoroughbreds have been shown to have longer right than left third metacarpal bones (the long bone in the front leg between the knee) and pastern (the joint immediately above the hoof). This could theoretically lead to advantages when racing on anticlockwise courses, and disadvantages on clockwise courses.

From the moment a foal first rises to her feet, she will tend to use one side of the body more than the other. Any innate bias can become consolidated as the foal grows.

When she goes into exercise training, the asymmetry persists, and may show in the horse’s behaviour.

Checking a horse’s movement

Side biases in the movement behaviour in the horse include the ease with which they flex their necks to the left or the right and, perhaps most importantly, their preferred leading leg in the canter and gallop.

Last year we published a study on more than 2,000 thoroughbred racehorses that established, for each horse, the lead-leg preference of the initial stride into gallop from the starting stalls.

Almost half (48.74%) of the horses started races in a direction counter to the optimal gallop leading leg and so would have to change leading leg to optimise their performance and safety on bends.

This increases the risk of errors on landing and therefore injuries. Injuries to horses also bring the risk of injury or even death for jockeys. Perhaps, when we have the right data, we will be able to confirm that Winx makes very few of these changes.

Let the tech detect the movement

Much recent research in horse biomechanics has used on-board accelerometry technology that can measure their movement while exercising freely in their natural environments at speeds near those in competition.

Studies have focused on gait characteristics – the way a horse moves – in normal and obviously lame horses and in other clinical conditions. It’s shown to be useful for accurate and sensitive detection of gait abnormality.

One study using accelerometry on 222 riding horses perceived as “healthy” by their owners found that 73% showed movement abnormalities during straight-line trotting.

Further studies using this technology should improve the welfare of performance horses and their riders if it can identify any gait abnormalities due to laterality, lameness, and other clinical problems.

Gait analysis will also reveal the attributes of horses that can safely and optimally race in both clockwise and anticlockwise directions, as Winx has shown.

So here’s hoping Winx can go out with another victory in her final race, at a sold-out event at Randwick (it’s a clockwise track and she’s had plenty of wins there).